Thursday, November 11, Happy Cloud Pictures shot a very tiny piece of what will be our sixth feature film. Those of you who have been along the HCP ride, with its odd twists and unexpected stops for maintenance and to transfer passengers, know how long this journey has been. We don’t choose our productions lightly and don’t leap blindly into the movie chasm, so we haven’t made anything we were ashamed of in thirteen years. But this new film is different, because it’s been alive almost as long as the company. (Almost. HCP formed in 1997 and we didn’t conceive the first draft of Razor Days until 2002, but it’s been alive, in one form or another, all of this time.) And now we’re finally in a position to make it.

I don’t want to give away too many details at the moment—yesterday I presented the story of its life in fairy-tale form—but I do want to say again that this is a different animal for us. We’re trying something different: a horror movie.

I’ve been saying for years that I don’t feel like we’ve really made a horror movie yet. We’ve done hybrids— comedy/horror, science fiction/horror, something-slash-horror. Razor Days is as much a thriller as it is a horror film, truth be told, but it’s still horror at the base. Horrific things happen and not all of them of the “ooh, cool effect!” variety. So I hope you’ll all bear with both my excitement and anxiety, since this was such a long time coming.

After a few months of wrangling and ironing out legal details, HCP formed a partnership with RAK Media, the publisher of Sirens of Cinema, to make Razor Days our first feature. There are grand plans for it, but it has to be made first. That first “production” step was taken on the aforementioned Thursday.

To announce officially, Razor Days stars Debbie Rochon, Amy Lynn Best, David Marancik (The Sadist), Jeff Monahan (Lone Star) and Alan Rowe Kelly (A Far Cry from Home), with Michael Varrati, Gwendolyn and fan-favorite Bill Homan making special appearances (as well as many of our HCP family members). Alan is also taking on a goodly portion of produce-orial duties. Robert Kuiper is the exec producer. Special Make-up designed by Gino Crognale (Sorority Row, Hostel III). Special props were created by Chris Pezzano. Cinematography would be conjured from the magical realm of electromagnetism by Dominick Sivilli (The Tell-Tale Heart) and Bart Mastronardi (Vindication). The bulk of filming will take place in the Spring of 2011.

But we all really wanted to get started sooner. So we got together and worked something out.

Two years ago, I covered George A. Romero Presents Deadtime Stories for Fangoria. Jeff Monahan wrote the three stories told in that upcoming anthology and directed one of the segments. He cast Amy in a cameo for the last story and we hung out on the set for the majority of that particularly shoot. Which took place in the historic Laurel Caverns outside of Uniontown , PA.

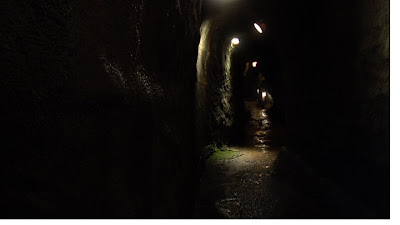

But the location is beautiful inside and out and I fell in love with the idea of shooting something there, and hey, our Razor Days script requires a cave setting! So what the heck, right?

We got the ball rolling back in July. First we needed to obtain permission. Then we had to make sure the partnership was in place, legally, so we could transfer our production insurance. Then came all the team building—assembling the right people with the right skills for the right time period, then figuring out how to get them down here and then what to do with them once they arrived. All the stuff I hate to deal with. Fortunately, Amy’s really good at all this stuff. So even though she’s one of the film’s stars, she undertook most of the pre-production duties.

All the big-picture stuff fell into place rather quickly, but the details started to dissolve. Our previous insurance company had restructured during the whole “economic clusterfuck” period, so we had to scramble to find new coverage. Fortunately, Alan was able to provide that solution after weeks of false starts. (This wasn’t an option—not only did we need to provide the cavern’s administrators with proof of coverage but we weren’t about to haul a dozen or so people 100 feet into the bowels of the Earth without making sure they’d be taken care of should a vicious cave troll eat their foot during filming!) But even with Alan’s guidance, we were still racing the clock and the calendar. The caverns are closed during the week after Labor Day, then close completely the weekend after Thanksgiving due to mountain snow causing untold amounts of potential death. The closer we got to Thanksgiving, the more we risked inclement weather, postponement of production and loss of mojo.

So I lit incense to Cinemagog, the God of Fillmmaking, and left out a dollar bill as an offering to Ifirs, the God of Executive Producing, in the hopes of getting these guys on our side. I also shouted to the heavens that I was not, nor could I possibly be confused with, Terry Gilliam, so they if they could see their way towards laying off, we’d be grateful.

The overall plan was to shoot as many of the little cave flashbacks as possible in as short a time as was feasible, then cobble together the footage for an extended trailer. It wasn’t a “film shoot” per ce as it was a trial run for the new family. Having met David Marancik and Dominick Sivilli socially, I’d never worked with them before. Alan had done some voice over work for me and sat for an interview for the Res. Game DVD, but we hadn’t done a project together. Heck, we’ve known Debbie for over a decade and shot five movies with her but for never more than a day or two at a time! So this was gonna be something new.

Fortunately, everyone likes everybody (and David). Plus, I had on hand the additional wonderful person of Michael Varrati, Razor Days’ publicist and HCP’s therapeutic counselor. He’s gotten through many a stressful convention and I felt confident he’d keep me from leaping off a ledge during filming.

So I don’t know if it was the incense, the begging, combined positive karma or if the universe was just in a particularly good mood last week, but the one-day shoot came off without a hitch and barely over budget! Alan, Dom and David were not killed in a horrible moose-crossing accident on their way from NY to PA. The Pittsburgh Airport did not give Debbie Ebola, the insurance company didn’t try to stick us for a dollar-per-dollar policy, the caverns did not fall in, explode or mysteriously move (though our GPS refused to actually get us there!) prior to our arrival (nor while we were there). In fact there was only one isolated bit of idiocy and that was on my end.

In the summer, I decided that HCP should upgrade its lighting kit. Perusing the wonderful digital garage sale that is Ebay, I came across a gorgeous little three-lamp halogen kit for a decent price. Ordered it, received it, looked at it, oohed, ahhed, and put the damn thing away. Without ever checking to see if the lamps had bulbs in them.

And, of course, they’re the kinds of bulbs made by Madagascan children, rolled on the thighs of plump Cuban women and only during the third full moon of the year and are not, therefore, available at Wal-Mart.

I don’t embarrass easily.

You know those dreams you have where you’re speaking in public and you realize you’re naked?

I get applause in those dreams.

But hanging out with a professional director of photography doing an equipment check and realizing that you didn’t—not once in three months—make sure you had light bulbs for your light kit—it’s a painful moment.

Dom rolled with it. Gave me a hug. Told me it would be okay. Realized that he had no way home without the other two. Told me it would be okay again. Thanks to Bill Homan and his 500 watt lighting kit, it was. But tell that to a drunk and sobbing me, crafting a noose out of old 16mm short ends!

Fortunately, the run-up to that was both relaxing and productive. After working part of the day and all of us rehearsing for the rest of Tuesday, Debbie, Amy and Michael sat down with their laptops and commenced a marathon Facebook chat, ending up with 200 posts on one thread. And if that isn’t a record… really, it should be. Meanwhile, I edited, chimed in when I had something incredibly witty to say, and endured Glee. Amy and Michael wanted to watch it, Debbie went to her happy place to avoid it; I wound up watching it. And paying attention to it. It was their “It Gets Better” episode. Meanwhile, we were all be-dogged by a quartet of canines confused by the company.

Wednesday night, prior to the humiliation brought about by lack of bulbs, Alan, David and Dom managed to reach Waynesburg unscathed and we had a production meeting over a Bob Evans dinner that was slightly less bland than not eating at all. It was then that I realized that we were lacking in specific set dressing. The cave is meant to be a cannibal lair. I had no bones. By which, I mean, external bones (x-rays have revealed me to be vertebrate, thank you).

Bill Homan to the rescue again. “How many do you need?” he asked. Which is not the first time such an ominous question was proffered to a ridiculous question. “A few,” I said. “A handful.”

“I don’t have hands,” he said. “I have legs and skulls and ribs and—”

The next morning, there was a large box waiting for me outside his house, filled to the brim with what used to be inside a small herd of Bambis. Like the cannibals in my story, however, Bill eats everything he kills, so he’s given a carnivore pass. Unlike the office bozos I’ve worked with in the past that just like to “kill stuff”.

Convinced I had left nothing else behind or unchecked, we led the caravan to the caverns. Michael and I sat in the backseat of the car, encumbered by heavy equipment, while Amy and Debbie drove in the front, less encumbered but laden with coffee. If any of you out there have ever met Amy or Debbie, you know that coffee is consumed by the oceanfuls. A week later and my house still smells like the inside of Juan Valdez’s bladder.

One grievous mistake made that cannot be solely attributed to me was the notion that we would accomplish more with a smallish crew. This was meant to be a fast, one-day shoot. Get in, get out. It was a paid shoot, all professional and everything, and we were hesitant to go too crazy over what would amount to about four minutes of footage and an ersatz trailer. So we’d all slap on our multiple hats and schlep cable, whip up craft services, provide make-up, “Hollywood” bounce boards and flags, whatever. Just the seven of us.

Do you know how long a walk 100 near-vertical feet is? You do? Are you over 30? You’re not? Then shut up, Mr. 127 Days. I’m still amazed that we met neither death-by-exhaustion nor a Minotaur during our frequent treks up and down that cavernous mountain. Because, of course, the room that wound up as everyone’s favorite was one of the furthest down from the visitor’s center and homebase. Glorious, grand, proof-of-God’s majesty, yeah, yeah, yeah. Still a long, steep fucking walk! And we all discovered our inner Indian (Cheroke, Ute or Algonquin—your preference) by getting lost at least once and following the light-kit wheel-tracks to freedom and sunlight again. Made us all feel smart and survivorish.

Photo by Amy Lynn Best

The temperature that deep in Laurel Caverns is about 50-55 degrees Fahrenheit year round. Which is fine in August. Coming in from 60 degrees outside to a ten-degree drop, stripping to the waist (in David’s case) or tied into limb-sleep stress positions (in Debbie’s case), and staying there for six hours well…Hey, Neil Marshall—you know what I’m talking about, right? Holla!

Anyway…

The benefit of shooting only flashbacks is that you can cheat a lot of things. Hairstyles don’t have to match precisely if there are other scenes between the shots you’re getting. The make-up can change. You can dictate the amount of time the characters are spending even if the script doesn’t spell it all out. The drawback is actually trying to figure all of that out and explaining it to everyone else when the script doesn’t spell it all out.

Actually, that was the biggest drawback of all, for me, at least: directing. I’ve joked in the past that actors are little more than “walking props”. I’ve often called the “noise bags” to the set when I’m ready to roll. And I’ve gone on and on how I much I dislike the actual production part of filmmaking. Let me write it, let me edit it, and tell me how all that middle stuff went. You know, for my blog.

But here we were, half-a-mile down in the belly of the Earth, the stars hoisting and toting along with the grips (which, that day, included Walt and Ian, two of the Caverns’ caretakers; the wonderful Doreen, who facilitated all of our desires, wisely stayed in the visitor’s center where it was saner—uh, warmer). Everyone was enduring the same chill, the same dirty conditions (the bowels of the Earth are just filthy!). And they kept asking me questions—endless questions—simply because I was the so-called director!

Now, since we started, Amy and I have always operated as a team. We’re like a married version of the Coen Brothers. Generally, even when I’m listed as “director”, Amy will work with the actors and I’ll work with the camera department. I’m just not an emotionally-giving guy. “I wrote the damned thing! It’s right there! What more do you need? Just do that!”

That’s not the best tactic, apparently.

And while the two of us had discussed the scenes ahead of time and the best way to play them, I was still, for all intents and purposes, directing the scenes. So I had to have answers. Which meant I had to know how to communicate those answers. “Act more!” would be unacceptable.

Photo by Amy Lynn Best

I was grateful that the first few shots we were doing were cutaways—close-ups of eyes, shoulders, props, things that formerly resided inside deer. All I had to do was say, “Great”, when Dominick asked me how I liked the framing. While he did that, Alan worked make-up and Amy did both producing and Best Boy work for Dom, I tried to figure out what the hell I was going to do.

Like I said: there was to be no cheating on this one. I couldn’t rely on Amy taking the reins with the actors as she did on Splatter Movie because she was going to need directing as well. I couldn’t fake my way through a scene with an Irish accent, joking and calling out “Gimme an Alien 3,” as I did on A Feast of Flesh. If everyone else was going to treat this like a hardcore professional film, I would have to as well. (This is not to belittle anyone else’s contribution to previous HCP films, nor to belittle the films themselves. We’ve never made anything I was anything less than sinfully proud of. This is all meant to bespeak of my attitude towards things. I rely on others to do excellent jobs. But now I had to leave the dugout, to use a barely-understood sports term.)

Photo by Amy Lynn Best

After the first couple of shots, we broke to set up for an elaborate take. We realized that something had been left behind “upstairs” and Amy took it upon herself to go running. “Direct your actors,” she told me and gave me a big smile. It was as much a pep talk as it was a suggestion. If you’ve been together with someone for sixteen years, you don’t need an “atta boy” every couple of minutes. But a well-timed one is always welcome.

There has only ever been one other moment in my life when the meaning of the word “directing” actually dawned on me, and that was a small test shoot in a hotel room after a convention, for a movie that never came together. But I had three professional actors before me who all needed to know specific things for the scene. Their questions crystallized the concept of “motivation” for me. The word wasn’t just a tired punchline. It wasn’t a prompt for the comeback “to get through the scene so we can go home”. “Motivation” is a single-word short-hand for “what is happening and what are we doing at this moment in time?” It also implies “what came before?” And I needed to have those answers.

Suddenly, I had them.

Everyone down in that cavern was a friend of mine; some for a very long time and some I’d only gotten close to recently. Half-a-mile beneath the surface of the Earth was a safe place then, because there was a common goal ahead of us. But if I was going to say that, for all intents and purposes, that I was the captain of this particular subterranean ship, then goddamn it, I’d better captain.

I forced myself to forget my own anxieties. I called upon what I knew of these people as both people and artists. I told them what I wanted.

Frame Grab - photography Dominick Sivilli

The first couple of times, I botched it. I’m not always the clearest of communicators, so it took me a few tries to find the right expressions to convey what was in my head. I had to dictate how these people felt. It’s not enough to say “Okay, you’re scared because this guy is doing this.” Of course you are. But scared how? For life and limb? To what degree? Terror or hysteria? And what else? Grief and shock? “You’re happy”. Yeah? Happy how?

Directing isn’t a con game. Friedkin can get away with shooting off a gun mid-take to get a reaction and Norman Taurog can threaten to shoot Jackie Cooper’s dog but that’s all smoke. That isn’t building a scene, that’s manipulation. That’s control, not shared art. If I wanted David to convey happiness, I couldn’t just buy him a puppy.

Frame Grab - photography Dominick Sivilli

Filmmaking isn’t like sex, as Peter Bogdanovich once said, because you never get to see anyone doing it, therefore you don’t know if you’re doing it right. It’s like sex because it’s different every single time. Even if you stick to the same positions, rhythm and timing, it’s still different because of chemistry, temperature and all other stimuli, internal and external. And you never really learn how to make a movie. You only learn how to make the movie you’re making. I still have some learning to come, but like a good joint, I knew right away when it hit me. Like any metaphor I’ve ever met, I found the right mix.

At least I think so. The footage looks gorgeous. We captured some amazing performances surrounded by gorgeous, natural surroundings (like in our other movies, this setting is going to be a character as well), production value you just can’t buy. And as exhausted as well all were at the end of the night, we were still friends. We’d gone through and come out the other side without egos taking the trip.

I could make the snide remark that Debbie and David had subjected us all to Tommy Wiseau’s monstrosity, The Room, the night before and if we’d left the lens cap on the camera we’d still have made a better movie than that—not to mention that if we can endure that hideousness as a family, we could survive anything.

But I won’t.

I’m just going to finish the edit of the teaser, start showing it around, get the damned thing some attention. Then in the Spring, we’ll return to work and wrap with something I have no doubt will be very special, a story worth telling.

And I’ll remember the bulbs next time. And hopefully the bones.